Gamification: A semester in the trenches

/

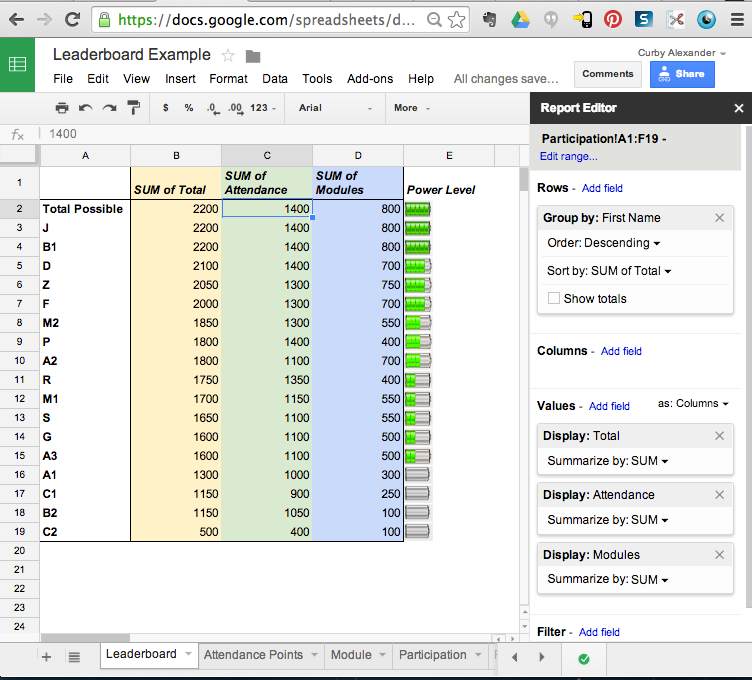

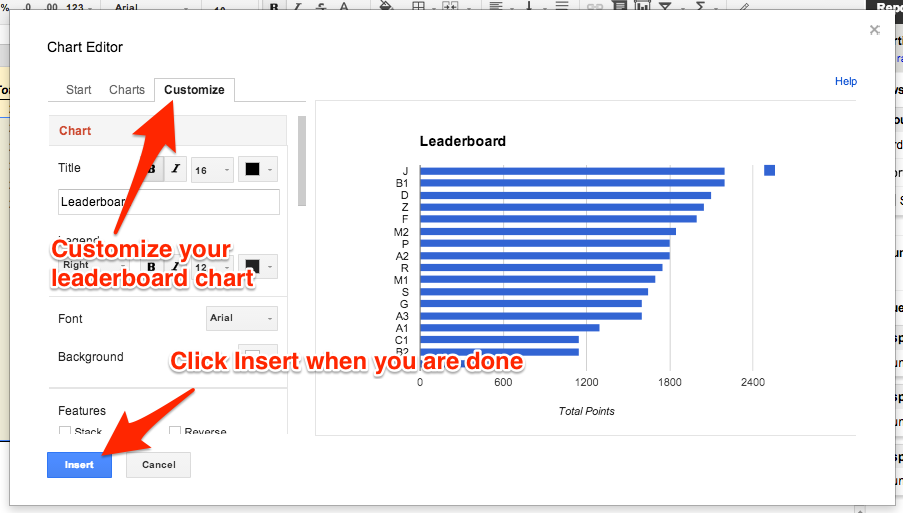

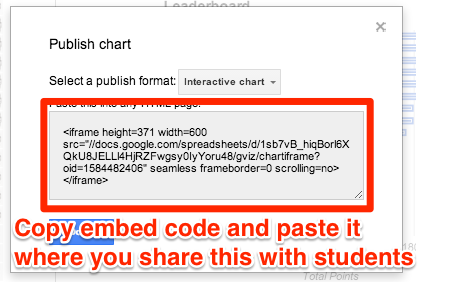

My reasons for wanting to use gamification strategies in my large Intro to Education course were obvious: student accountability, timely and continuous feedback, and better motivation to do otherwise rudimentary activities. I learned pretty quickly that implementing gamification strategies was more difficult than I initially thought. First, I had to figure out the instructional design aspects of gamification. How many points are different experiences worth? What do I count and what do I leave out? Second, I had to figure out how to keep track of all of this and communicate it back to the students. As I have written about before, I used Google Sheets to do this.

Overall, I would say I am pleased with how my first attempt at gamification turned out. Was it perfect? No way. Did the students like it? Mostly, but I'm sure I will hear from those who didn't on my course evaluations. Did these strategies help me reach my course goals? Absolutely! Class attendance was the best it has ever been in the 3 years I've taught the course. I regularly had over 90% of the students completing the weekly readings every week. That is unbelievable! I actually had students competing to complete extra credit so they could move to the top of the leaderboard. I did not see that one coming. Even though the course outcomes associated with these gamification strategies were successful, I learned a lot about how to do it better next semester. I will discuss these lessons in more detail.

More Competition

One of my goals in using gamification strategies in my class was to increase engagement and not give students a laundry list of things to do every week. Well, the way I structured the points, it turned out to be just what I was trying to avoid. Every week the students had to complete a module (video and/or reading + short quiz) before class on Monday. Then they went to schools on Wednesday, and there were points associated with that. On Friday, they participated in small group discussion, which had even more points. Everything was recorded on a big spreadsheet, and students were ranked on a leaderboard. What I discovered was that most of the students completed all of the requirements each week. Basically, there was no way to really move UP the leaderboard. Students could only move DOWN if they failed to complete a requirement. Believe it or not, that is not very competitive, and therefore, isn't all that much fun.

There were minimal opportunities for students to do extra and move up the leaderboard, but they were in fact so minimal that it hardly made a difference. This didn't keep the students from trying to get more points here and there, which was my first clue that there needs to be more competition. Some ideas I am playing with include:

- Using Kahoot for discussion questions

- Students voting for "best" responses to questions

- Competitions between discussion groups (attendance, challenges, completion rate, etc.)

- Challenges during class

I do not want to overdo this, but I think a little more competition would make this aspect of the class a lot more fun.

Reboot

Another flaw in my approach this semester was that the "game" lasted all semester. I gave the students monthly feedback in the form of a points sheet, which led many of them to just see it as a big assignment. I would venture to guess that they viewed this experiment as a big ole' laundry list because I treated it like one. In the end, there was no way for students who had gotten behind early in the semester to make corrections and do better the next time around. Students could recognize the impact of their choices on their point total and start to do better, but it did not erase early mistakes. This goes against the nature of most competitive endeavors, where players can overcome early mistakes later in the competition and keep themselves in the game.

I am thinking about splitting the game up into three smaller games this spring, and starting the points and leaderboard over each time. This will allow students who get off to a bad start to do better the next time. I can still keep track of completed assignments and attendance for the purposes of grading, but I will link other incentives to the leaderboard. What are the incentives? I have no idea, but I have a few weeks to think about it.

Better Feedback

Another issue I ran into this semester was getting feedback to the students on a weekly basis. I did pretty well at first, then some of my TAs got behind on entering scores and I went a few weeks without sending updates to the class. Once everything was updated and I got around to sending the updates, some of the students were like, "Whoa! How did I lose all these points?! I thought I was doing OK!" And I was like, "How can you not know if you missed class or an assignment?!" And they were like, "Hey man, we're too busy to remember all that!" And I was like ... OK, you get the point.

This observation has less to do with the game itself and more to do with giving more timely, detailed feedback. Some of the students felt like they were in the dark all semester and did not know they had missed 6, 7, or 8 classes until the end of the semester. I was never the kind of student to miss class, but I can see how it might be easy to lose track over such a long period of time.

I have a plan for keeping the spreadsheet updated better, but it is not really worth writing about here. Needless to say, I think weekly updates will help quell some of the panicky e-mails at the end of the semester.

What am I missing?

I am pretty sure my second attempt at gamification will go much better than the first, and I'm looking forward to putting some of these ideas into practice. For those of you who have been doing this for awhile, what are your suggestions? Am I missing something obvious? Am I making assumptions with potentially disastrous consequences? I would love to hear from the true game masters!

Turning something into a game does not necessarily mean people will suddenly like it. Atari learned this the hard way with their

Turning something into a game does not necessarily mean people will suddenly like it. Atari learned this the hard way with their

It's that time of year again, when I spend a lot of time reflecting on the semester and academic year. I have already

It's that time of year again, when I spend a lot of time reflecting on the semester and academic year. I have already  I have been teaching for nearly 20 years, and I have seen just about everything. Throughout the many life changes I have experienced in that time, teaching, oddly enough, has been one of the constants in my life. Early in my career I would stay late at school and come home to an empty apartment. Soon enough, I was finding ways to have lunch with my wife over our short lunch breaks. Then I was rushing home after teaching so I could spend time with my babies. Now I have to be creative in order to balance my teaching with things like baseball, gymnastics, theater classes, church, committees, writing, and staying connected to family. During all this time, students have come and gone from my classes, hopefully taking something with them that will help in their life journey.

I have been teaching for nearly 20 years, and I have seen just about everything. Throughout the many life changes I have experienced in that time, teaching, oddly enough, has been one of the constants in my life. Early in my career I would stay late at school and come home to an empty apartment. Soon enough, I was finding ways to have lunch with my wife over our short lunch breaks. Then I was rushing home after teaching so I could spend time with my babies. Now I have to be creative in order to balance my teaching with things like baseball, gymnastics, theater classes, church, committees, writing, and staying connected to family. During all this time, students have come and gone from my classes, hopefully taking something with them that will help in their life journey.