Something old. Something new. Something borrowed. And something ... green?

/I recently had a great conversation with my doctoral advisor, and he tuned me into Xtranormal, a fairly simple tool that lets you create short animations by typing in text and dragging in motions and other effects. My first project was to see if I could even work with this tool. The interface is pretty intuitive and I made this movie without having to go back and start over (too many times).

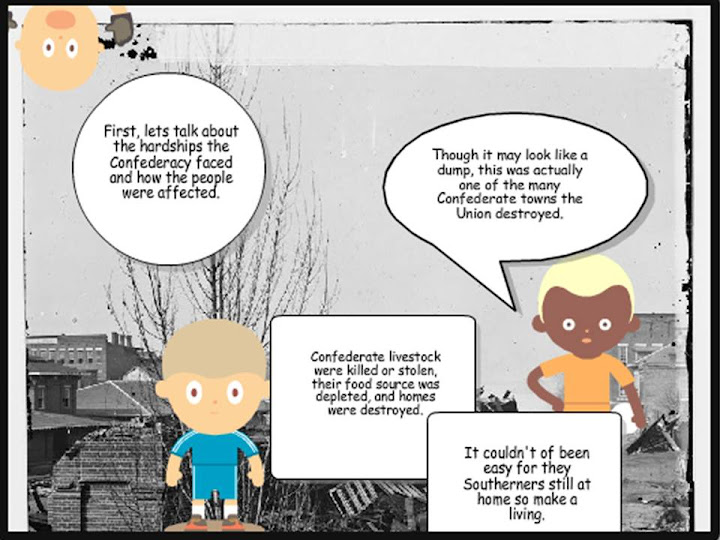

As I was playing around, I noticed that one of the pre-made scenes had a green screen as the background. This reminded me of my first trip to Universal Studios, and how they made it look like ET and Elliot were flying through the air on a bicycle. I wanted to see if I could recreate one of the scenes made by one of the participants in my dissertation study. Here is the original scene from the storyboard:

I then recreated this scene using the green screen as my background:

This is where things got a little complicated and pretty sloppy. In order to add the background to the animation, I had to download the video file onto my computer. First, I had to move the movie to my Youtube account, which was pretty easy. Then I downloaded the file using mediaconverter.org. This was pretty simple, as well. Using Adobe Premier and some built in hocus-pocus, I was able to put a historical image as the background. The final version is pretty rough (probably because of all the downloading, converting and re-converting), but you can get a glimpse of the idea below:

The whole process was pretty labor intensive, even for a short clip like this, but it at least opens the door for some future projects on how to mashup historical documents with new media.